Saturday, October 31, 2015

A Tale to Tremble By

This month I have been obsessing over some of my favorite Halloween books, particularly the Tales to Tremble By anthologies of my childhood. The books are long out of print, but the stories within are all in the public domain and can be found in one format or another on the Internet. I had this crazy idea that I would collect them all and make them into an e-book for my Kindle.

Last week I shared the story I had the most difficulty tracking down: the anonymous Scottish tale of The Sutor of Selkirk. This week I present one that was very easy to find: Adventure of the German Student, by Washington Irving—yes, the same Washington Irving who wrote The Legend of Sleepy Hollow. In my opinion, the following story is far more horrifying than that of the Headless Horseman. Although you will no doubt quickly realize where the story is headed (heh-heh), the ending is still shocking. I'm sure it gave me nightmares when I read it fifty years ago, and it still has an impact when I read it now.

Enjoy the story, and if you have a Kindle and would like to read all of the stories from Tales to Tremble By and More Tales to Tremble By, you are welcome to download my AZW3 file, here. After downloading the file, copy it to your Kindle using these instructions. Better yet, download and install Calibre, the shareware I used to create my e-book. Calibre is an excellent tool for creating, editing, and organizing e-books. Think of it as iTunes for e-books; when you connect your Kindle (or other e-reader) to your computer, Calibre automatically recognizes it and allows you to easily transfer your e-books in the same way iTunes allows you to transfer music files to your iPod or iPhone. You can also use Calibre to convert my AZW3 file to another format, such as EPUB, PDF, or RTF.

Happy Halloween!

Adventure of the German Student

by Washington Irving

On a stormy night, in the tempestuous times of the French Revolution, a young German was returning to his lodgings, at a late hour, across the old part of Paris. The lightning gleamed, and the loud claps of thunder rattled through the lofty narrow streets—but I should first tell you something about this young German.

Gottfried Wolfgang was a young man of good family. He had studied for some time at Göttingen, but being of a visionary and enthusiastic character, he had wandered into those wild and speculative doctrines which have so often bewildered German students. His secluded life, his intense application, and the singular nature of his studies, had an effect on both mind and body. His health was impaired; his imagination diseased. He had been indulging in fanciful speculations on spiritual essences, until, like Swedenborg, he had an ideal world of his own around him. He took up a notion, I do not know from what cause, that there was an evil influence hanging over him; an evil genius or spirit seeking to ensnare him and ensure his perdition. Such an idea working on his melancholy temperament produced the most gloomy effects. He became haggard and desponding. His friends discovered the mental malady preying upon him, and determined that the best cure was a change of scene; he was sent, therefore, to finish his studies amidst the splendours and gaieties of Paris.

Wolfgang arrived at Paris at the breaking out of the revolution. The popular delirium at first caught his enthusiastic mind, and he was captivated by the political and philosophical theories of the day: but the scenes of blood which followed shocked his sensitive nature, disgusted him with society and the world, and made him more than ever a recluse. He shut himself up in a solitary apartment in the Pays Latin, the quarter of students. There, in a gloomy street not far from the monastic walls of the Sorbonne, he pursued his favorite speculations. Sometimes he spent hours together in the great libraries of Paris, those catacombs of departed authors, rummaging among their hoards of dusty and obsolete works in quest of food for his unhealthy appetite. He was, in a manner, a literary ghoul, feeding in the charnel-house of decayed literature.

Wolfgang, though solitary and recluse, was of an ardent temperament, but for a time it operated merely upon his imagination. He was too shy and ignorant of the world to make any advances to the fair, but he was a passionate admirer of female beauty, and in his lonely chamber would often lose himself in reveries on forms and faces which he had seen, and his fancy would deck out images of loveliness far surpassing the reality.

While his mind was in this excited and sublimated state, a dream produced an extraordinary effect upon him. It was of a female face of transcendent beauty. So strong was the impression made, that he dreamt of it again and again. It haunted his thoughts by day, his slumbers by night; in fine, he became passionately enamored of this shadow of a dream. This lasted so long that it became one of those fixed ideas which haunt the minds of melancholy men, and are at times mistaken for madness.

Such was Gottfried Wolfgang, and such his situation at the time I mentioned. He was returning home late one stormy night, through some of the old and gloomy streets of the Marais, the ancient part of Paris. The loud claps of thunder rattled among the high houses of the narrow streets. He came to the Place de Grève, the square, where public executions are performed. The lightning quivered about the pinnacles of the ancient Hôtel de Ville, and shed flickering gleams over the open space in front. As Wolfgang was crossing the square, he shrank back with horror at finding himself close by the guillotine. It was the height of the reign of terror, when this dreadful instrument of death stood ever ready, and its scaffold was continually running with the blood of the virtuous and the brave. It had that very day been actively employed in the work of carnage, and there it stood in grim array, amidst a silent and sleeping city, waiting for fresh victims.

Wolfgang’s heart sickened within him, and he was turning shuddering from the horrible engine, when he beheld a shadowy form, cowering as it were at the foot of the steps which led up to the scaffold. A succession of vivid flashes of lightning revealed it more distinctly. It was a female figure, dressed in black. She was seated on one of the lower steps of the scaffold, leaning forward, her face hid in her lap; and her long dishevelled tresses hanging to the ground, streaming with the rain which fell in torrents. Wolfgang paused. There was something awful in this solitary monument of woe. The female had the appearance of being above the common order. He knew the times to be full of vicissitude, and that many a fair head, which had once been pillowed on down, now wandered houseless. Perhaps this was some poor mourner whom the dreadful axe had rendered desolate, and who sat here heart-broken on the strand of existence, from which all that was dear to her had been launched into eternity.

He approached, and addressed her in the accents of sympathy. She raised her head and gazed wildly at him. What was his astonishment at beholding, by the bright glare of the lightning, the very face which had haunted him in his dreams. It was pale and disconsolate, but ravishingly beautiful.

Trembling with violent and conflicting emotions, Wolfgang again accosted her. He spoke something of her being exposed at such an hour of the night, and to the fury of such a storm, and offered to conduct her to her friends. She pointed to the guillotine with a gesture of dreadful signification.

“I have no friend on earth!” said she.

“But you have a home,” said Wolfgang.

“Yes—in the grave!”

The heart of the student melted at the words.

“If a stranger dare make an offer,” said he, “without danger of being misunderstood, I would offer my humble dwelling as a shelter; myself as a devoted friend. I am friendless myself in Paris, and a stranger in the land; but if my life could be of service, it is at your disposal, and should be sacrificed before harm or indignity should come to you.”

There was an honest earnestness in the young man’s manner that had its effect. His foreign accent, too, was in his favor; it showed him not to be a hackneyed inhabitant of Paris. Indeed, there is an eloquence in true enthusiasm that is not to be doubted. The homeless stranger confided herself implicitly to the protection of the student.

He supported her faltering steps across the Pont Neuf, and by the place where the statue of Henry the Fourth had been overthrown by the populace. The storm had abated, and the thunder rumbled at a distance. All Paris was quiet; that great volcano of human passion slumbered for a while, to gather fresh strength for the next day’s eruption. The student conducted his charge through the ancient streets of the Pays Latin, and by the dusky walls of the Sorbonne, to the great dingy hotel which he inhabited. The old portress who admitted them stared with surprise at the unusual sight of the melancholy Wolfgang, with a female companion.

On entering his apartment, the student, for the first time, blushed at the scantiness and indifference of his dwelling. He had but one chamber—an old-fashioned saloon—heavily carved, and fantastically furnished with the remains of former magnificence, for it was one of those hotels in the quarter of the Luxembourg palace which had once belonged to nobility. It was lumbered with books and papers, and all the usual apparatus of a student, and his bed stood in a recess at one end.

When lights were brought, and Wolfgang had a better opportunity of contemplating the stranger, he was more than ever intoxicated by her beauty. Her face was pale, but of a dazzling fairness, set off by a profusion of raven hair that hung clustering about it. Her eyes were large and brilliant, with a singular expression approaching almost to wildness. As far as her black dress permitted her shape to be seen, it was of perfect symmetry. Her whole appearance was highly striking, though she was dressed in the simplest style. The only thing approaching to an ornament which she wore, was a broad black band round her neck, clasped by diamonds.

The perplexity now commenced with the student how to dispose of the helpless being thus thrown upon his protection. He thought of abandoning his chamber to her, and seeking shelter for himself elsewhere. Still he was so fascinated by her charms, there seemed to be such a spell upon his thoughts and senses, that he could not tear himself from her presence. Her manner, too, was singular and unaccountable. She spoke no more of the guillotine. Her grief had abated. The attentions of the student had first won her confidence, and then, apparently, her heart. She was evidently an enthusiast like himself, and enthusiasts soon understand each other.

In the infatuation of the moment, Wolfgang avowed his passion for her. He told her the story of his mysterious dream, and how she had possessed his heart before he had even seen her. She was strangely affected by his recital, and acknowledged to have felt an impulse towards him equally unaccountable. It was the time for wild theory and wild actions. Old prejudices and superstitions were done away; everything was under the sway of the “Goddess of Reason.” Among other rubbish of the old times, the forms and ceremonies of marriage began to be considered superfluous bonds for honorable minds. Social compacts were the vogue. Wolfgang was too much of theorist not to be tainted by the liberal doctrines of the day.

“Why should we separate?” said he: “our hearts are united; in the eye of reason and honor we are as one. What need is there of sordid forms to bind high souls together?”

The stranger listened with emotion: she had evidently received illumination at the same school.

“You have no home nor family,” continued he: “Let me be everything to you, or rather let us be everything to one another. If form is necessary, form shall be observed—there is my hand. I pledge myself to you forever.”

“Forever?” said the stranger, solemnly.

“Forever!” repeated Wolfgang.

The stranger clasped the hand extended to her: “Then I am yours,” murmured she, and sank upon his bosom.

The next morning the student left his bride sleeping, and sallied forth at an early hour to seek more spacious apartments suitable to the change in his situation. When he returned, he found the stranger lying with her head hanging over the bed, and one arm thrown over it. He spoke to her, but received no reply. He advanced to awaken her from her uneasy posture. On taking her hand, it was cold—there was no pulsation—her face was pallid and ghastly. In a word, she was a corpse.

Horrified and frantic, he alarmed the house. A scene of confusion ensued. The police was summoned. As the officer of police entered the room, he started back on beholding the corpse.

“Great heaven!” cried he, “how did this woman come here?”

“Do you know anything about her?” said Wolfgang eagerly.

“Do I?” exclaimed the officer: “she was guillotined yesterday.”

He stepped forward; undid the black collar round the neck of the corpse, and the head rolled on the floor!

The student burst into a frenzy. “The fiend! the fiend has gained possession of me!” shrieked he; “I am lost forever.”

They tried to soothe him, but in vain. He was possessed with the frightful belief that an evil spirit had reanimated the dead body to ensnare him. He went distracted, and died in a mad-house.

Here the old gentleman with the haunted head finished his narrative.

“And is this really a fact?” said the inquisitive gentleman.

“A fact not to be doubted,” replied the other. “I had it from the best authority. The student told it me himself. I saw him in a mad-house in Paris.”

Saturday, October 24, 2015

Googling a Gaelic Ghost

As I mentioned earlier this month, among my favorite books for the Halloween season are two horror anthologies by Stephen Sutton: Tales to Tremble By and More Tales to Tremble By. After writing about these childhood favorites, I suddenly had the urge to read them again. I knew I had them somewhere, tucked among the hundreds of books in one of several bookcases in the house, or possibly in a box in the garage. I made a perfunctory search, but I was not able to find them. Even if I had been able to find them, since I have gotten used to reading on a Kindle, I no longer care to carry books around with me (especially books that are nearly as old and fragile as I am).

If only I could find TtTB and MTtTB in Kindle format.

Unfortunately, both books are out of print and will probably never be re-released—either for Kindle or in any other format. However, the stories in them were ancient when I first read them fifty years ago. If they weren't in the public domain then, they must be by now. Perhaps I could find them online and create my own Kindle book! I found lists of all the stories contained in each volume, and I began my search. Sure enough, within a week I had found every story but one: "The Suitor of Selkirk" by Anonymous.

Anonymous. Do you have any idea how difficult it is to find a story that has no author?

I considered giving up. After all, I had found most of the stories from TtTB and all of the stories from MTtTB. But I was obsessed. Who was this Suitor of Selkirk? The ghost of a star-crossed lover? The ghost of a petitioner in a lawsuit? I must have read the story as a child, but for the life of me I could not remember it, and I had to know.

I found one other reference to the story in a review of a 1935 horror anthology: More Great Tales of Horror, by Marjorie Bowen (aka Margaret Gabrielle Vere Campbell Long). Unfortunately, I could not find an electronic version of MGToH, either. However, the description of it told me that the story was originally from something called The Odd Volume. When I searched for "suitor of selkirk odd volume," Google informed me that it was also "Including results for sutor of selkirk odd volume." (This is why I use Google. Would Yahoo or Bing have gone that extra mile? I don't think so.)

I Googled the word "sutor" and found that it meant "a cobbler or shoemaker." By this time, I had also found my copy of TtTB. (It had been on a shelf not three feet from my head, hidden behind another row of books.) Sure enough, the story was actually titled "The Sutor of Selkirk," and was the account of a Scottish shoemaker's encounter with a mysterious customer. Someone had mistakenly corrected "sutor" to "suitor" in references to the contents of both TtTB and MGToH.

Once I had the spelling of "sutor" right, I immediately found the story posted on a site called Electric Scotland. That version had been scanned from an 1896 volume: The Book of Scottish Story. I also found it in an 1829 volume of The Edinburgh Literary Journal, scanned by Google Books. Both versions looked to be the same, and were considerably more Scottish than the version in TtTB. Somewhere along the way, someone had anglicized many of the more obscure expressions. (I suspect Marjorie Bowen, aka Margaret Gabrielle Vere Campbell Long. Anyone with that many names can't be trusted.)

For example, “He smells awfully o’ yird,” was changed to simply, “He smells awfully,” which gives the sentence a completely different meaning. It indicates the sutor's mysterious customer has an inferior sense of smell. (Which, come to think of it, he probably does, being dead.*

The complete story is below. I corrected a few typos and scan errors, but I left all of the Scottish expressions intact. You should be able to figure out their meaning from the context; if not, there's always Google. It's a fine ghost story full of wry gallows humor, and well worth the extra effort.

I will tell you this much: "yird" means "earth."

The Sutor of Selkirk: A Remarkably True Story

Once upon a time, there lived in Selkirk a shoemaker, by name Rabbie Heckspeckle, who was celebrated both for dexterity in his trade, and for some other qualifications of a less profitable nature. Rabbie was a thin, meagre-looking personage, with lank black hair, a cadaverous countenance, and a long, flexible, secret-smelling nose. In short, he was the Paul Pry of the town. Not an old wife in the parish could buy a new scarlet rokelay without Rabbie knowing within a groat of the cost; the doctor could not dine with the minister but Rabbie could tell whether sheep’s-head or haggis formed the staple commodity of the repast; and it was even said that he was acquainted with the grunt of every sow, and the cackle of every individual hen, in his neighbourhood; but this wants confirmation. His wife, Bridget, endeavoured to confine his excursive fancy, and to chain him down to his awl, reminding him it was all they had to depend on; but her interference met with exactly that degree of attention which husbands usually bestow on the advice tendered by their better halves—that is to say, Rabbie informed her that she knew nothing of the matter, that her understanding required stretching, and finally, that if she presumed to meddle in his affairs, he would be under the disagreeable necessity of giving her a top-dressing.

To secure the necessary leisure for his researches, Rabbie was in the habit of rising to his work long before the dawn; and he was one morning busily engaged putting the finishing stitches to a pair of shoes for the exciseman, when the door of his dwelling, which he thought was carefully fastened, was suddenly opened, and a tall figure, enveloped in a large black cloak, and with a broad-brimmed hat drawn over his brows, stalked into the shop. Rabbie stared at his visitor, wondering what could have occasioned this early call, and wondering still more that a stranger should have arrived in the town without his knowledge.

“You’re early afoot, sir,” quoth Rabbie. “Lucky Wakerife’s cock will no craw for a good half hour yet.”

The stranger vouchsafed no reply; but taking up one of the shoes Rabbie had just finished, deliberately put it on, and took a turn through the room to ascertain that it did not pinch his extremities. During these operations, Rabbie kept a watchful eye on his customer.

“He smells awfully o’ yird,” muttered Rabbie to himself; “ane would be ready to swear he had just cam frae the plough-tail.”

The stranger, who appeared to be satisfied with the effect of the experiment, motioned to Rabbie for the other shoe, and pulled out a purse for the purpose of paying for his purchase; but Rabbie’s surprise may be conceived, when, on looking at the purse, he perceived it to be spotted with a kind of earthy mould.

“Gudesake,” thought Rabbie, “this queer man maun hae howkit that purse out o’ the ground. I wonder where he got it. Some folk say there are bags o’ siller buried near this town.”

By this time the stranger had opened the purse, and as he did so, a toad and a beetle fell on the ground, and a large worm crawling out wound itself round his finger. Rabbie’s eyes widened; but the stranger, with an air of nonchalance, tendered him a piece of gold, and made signs for the other shoe.

“It’s a thing morally impossible,” responded Rabbie to this mute proposal. “Mair by token, that I hae as good as sworn to the exciseman to hae them ready by daylight, which will no be long o’ coming” (the stranger here looked anxiously towards the window); “and better, I tell you, to affront the king himsel, than the exciseman.”

The stranger gave a loud stamp with his shod foot, but Rabbie stuck to his point, offering, however, to have a pair ready for his new customer in twenty-four hours; and, as the stranger, justly enough perhaps, reasoned that half a pair of shoes was of as little use as half a pair of scissors, he found himself obliged to come to terms, and seating himself on Rabbie’s three-legged stool, held out his leg to the Sutor, who, kneeling down, took the foot of his taciturn customer on his knee, and proceeded to measure it.

“Something o’ the splay, I think, sir,” said Rabbie, with a knowing air.

No answer.

“Where will I bring the shoon to when they’re done?” asked Rabbie, anxious to find out the domicile of his visitor.

“I will call for them myself before cock crowing,” responded the stranger in a very uncommon and indescribable tone of voice.

“Hout, sir,” quoth Rabbie, “I canna let you hae the trouble o’ coming for them yoursel; it will just be a pleasure for me to call with them at your house.”

“I have my doubts of that,” replied the stranger, in the same peculiar manner; “and at all events, my house would not hold us both.”

“It maun he a dooms sma’ biggin,” answered Rabbie; “but noo that I hae ta’en your honour’s measure—”

“Take your own!” retorted the stranger, and giving Rabbie a touch with his foot that laid him prostrate, walked coolly out of the house.

This sudden overturn of himself and his plans for a few moments discomfited the Sutor; but quickly gathering up his legs, he rushed to the door, which he reached just as Lucky Wakerife’s cock proclaimed the dawn. Rabbie flow down the street, but all was still; then ran up the street, which was terminated by the churchyard, but saw only the moveless tombs looking cold and chill under the grey light of a winter morn. Rabbie hitched his red nightcap off his brow, and scratched his head with an air of perplexity.

“Weel” he muttered, as he retraced his steps homewards, “he has warred me this time, but sorrow take me if I’m no up wi’ him the morn.”

All day Rabbie, to the inexpressible surprise of his wife, remained as constantly on his three-legged stool as if he had been “yirked” there by some brother of the craft. For the space of twenty-four hours, his long nose was never seen to throw its shadow across the threshold of the door; and so extraordinary did this event appear, that the neighbours, one and all, agreed that it predicted some prodigy; but whether it was to take the shape of a comet, which would deluge them all with its fiery tail, or whether they were to be swallowed up by an earthquake, could by no means be settled to the satisfaction of the parties concerned.

Meanwhile, Rabbie diligently pursued his employment, unheeding the concerns of his neighbours. What mattered it to him, that Jenny Thrifty’s cow had calved, that the minister’s servant, with something in her apron, had been seen to go in twice to Lucky Wakerife’s, that the laird’s dairy-maid had been observed stealing up the red loan in the gloaming, that the drum had gone through the town announcing that a sheep was to be killed on Friday?—The stranger alone swam before his eyes; and cow, dairymaid, and drum kicked the beam. It was late in the night when Rabbie had accomplished his task, and then placing the shoes at his bedside, he lay down in his clothes, and fell asleep; but the fear of not being sufficiently alert for his new customer, induced him to rise a considerable time before daybreak. He opened the door and looked into the street, but it was still so dark he could scarcely see a yard before his nose; he therefore returned into the house, muttering to himself—“What the sorrow can keep him?” when a voice at his elbow suddenly said—

“Where are my shoes?”

“Here, sir,” said Rabbie, quite transported with joy; “here they are, right and tight, and mickle joy may ye hae in wearing them, for it’s better to wear shoon than sheets, as the auld saying gangs.”

“Perhaps I may wear both,” answered the stranger.

“Gude save us,” quoth Rabbie, “do ye sleep in your shoon?”

The stranger made no answer; but, laying a piece of gold on the table and taking up the shoes, walked out of the house.

“Now’s my time.” thought Rabbie to himself, as he slipped after him.

The stranger paced slowly on, and Rabbie carefully followed him; the stranger turned up the street, and the Sutor kept close to his heels. “’Odsake, where can he be gaun?” thought Rabbie, as he saw the stranger turn into the churchyard; “he’s making to that grave in the corner; now he’s standing still; now he’s sitting down. Gudesake! what’s come o’ him?” Rabbie rubbed his eyes, looked round in all directions, but, lo and behold! the stranger had vanished. “There’s something no canny about this,” thought the Sutor; “but I’ll mark the place at ony rate;” and Rabbie, after thrusting his awl into the grave, hastily returned home.

|

| Shannon Stirnweis's illustration from TtTB |

Certain qualms of conscience, however, now arose in Rabbie’s mind as to the propriety of depriving the corpse of what had been honestly bought and paid for. He could not help allowing, that if the ghost were troubled with cold feet, a circumstance by no means improbable, he might naturally wish to remedy the evil. But, at the same time, considering that the fact of his having made a pair of shoes for a defunct man would be an everlasting blot on the Heckspeckle escutcheon, and reflecting also that his customer, being dead in law, could not apply to any court for redress, our Sutor manfully resolved to abide by the consequences of his deed.

Next morning, according to custom, he rose long before day, and fell to his work, shouting the old song of the “Sutors of Selkirk” at the very top of his voice. A short time, however, before the dawn, his wife, who was in bed in the back room, remarked, that in the very middle of his favourite verse, his voice fell into a quaver; then broke out into a yell of terror; and then she heard a noise, as of persons struggling; and then all was quiet as the grave. The good dame immediately huddled on her clothes, and ran into the shop, where she found the three-legged stool broken in pieces, the floor strewed with bristles, the door wide open, and Rabbie away! Bridget rushed to the door, and there she immediately discovered the marks of footsteps deeply printed on the ground. Anxiously tracing them, on—and on—and on— what was her horror to find that they terminated in the churchyard, at the grave of Rabbie’s customer! The earth round the grave bore traces of having been the scene of some fearful struggle, and several locks of lank black hair were scattered on the grass. Half distracted, she rushed through the town to communicate the dreadful intelligence. A crowd collected, and a cry speedily arose to open the grave. Spades, pickaxes, and mattocks, were quickly put in requisition; the divots were removed; the lid of the coffin was once more torn off, and there lay its ghastly tenant, with his shoes replaced on his feet, and Rabbie’s red night-cap clutched in his right hand!

The people, in consternation, fled from the churchyard; and nothing further has ever transpired to throw any additional light upon the melancholy fate of the Sutor of Selkirk.

Footnote

* Sorry, I probably should have included a spoiler alert there. ("Spoiler alert." That's actually pretty funny. Get it? Spoiler alert? Because he's dead? Never mind. Sorry I brought it up.)

Saturday, October 17, 2015

A Few Interesting Facts About Halloween

Most of the following facts come from The Book of Halloween, by Edna Kelley, A.M.,1 published in 1919. I mentioned this book in a previous post. At the time, I had not read it. Now I have, and hoo-boy, is it boring! However, it does contain a few interesting facts. For instance:

The Origin of Halloween

Halloween was invented by the Celts, an ancient people who inhabited what is now Ireland, Great Britain, and part of France. Of course, the Celts did not call it "Halloween." They called it "Samhain," a word which nobody can agree on the pronunciation of, except that it is definitely not pronounced "Samhain."

Halloween was invented by the Celts, an ancient people who inhabited what is now Ireland, Great Britain, and part of France. Of course, the Celts did not call it "Halloween." They called it "Samhain," a word which nobody can agree on the pronunciation of, except that it is definitely not pronounced "Samhain."When the Romans invaded the Celts, they did not approve of their religion.2 They unsuccessfully tried to eliminate it by killing off the Celtic priests, who were known as "Druids."3 After the Romans became Christians, they again tried to wipe out the Celts' religion—this time more successfully—by repurposing their pagan holidays as Christian ones.4 Samhain became "All Saints' Day" or "All Hallows' Day," and the night before became "All Hallows' Eve." Later, this was shortened to "Hallowe'en." Still later, the apostrophe was dropped.5

Halloween Customs

There are many Halloween customs involving food, most of them having to do with foretelling whether or not one will find a mate. For example, if a young man successfully sticks his head in a tub of water and grabs an apple with his teeth, "his love affair will end happily."6 If he finds the ring, coin, or thimble concealed in his mashed potatoes or cake, he "will be married in a year, or if he is already married, will be lucky."7 Burning nuts can also be used to prognosticate one's love life, but it's a complicated process, and I won't go into it here.

There are many Halloween customs involving food, most of them having to do with foretelling whether or not one will find a mate. For example, if a young man successfully sticks his head in a tub of water and grabs an apple with his teeth, "his love affair will end happily."6 If he finds the ring, coin, or thimble concealed in his mashed potatoes or cake, he "will be married in a year, or if he is already married, will be lucky."7 Burning nuts can also be used to prognosticate one's love life, but it's a complicated process, and I won't go into it here.Speaking of burning nuts, there are also many Halloween customs involving a dangerous proximity to fire. Bonfires were common, and of course candles were stuck inside gourds and turnips to make jack-o-lanterns. Candles were also used in party games: "In an old book there is a picture of a youth sitting on a stick placed across two stools. On one end of the stick is a lighted candle from which he is trying to light another in his hand." Imagine the excitement!8

Trick-or-Treating

I'm not sure the term "trick-or-treating" was in use when Edna Kelley wrote The Book of Halloween. She never mentions it, although she does mention tricks: "It is a night of ghostly and merry revelry. Mischievous spirits choose it for carrying off gates and other objects, and hiding them or putting them out of reach."

|

| Adorable Pumpkin-Headed Mutants Steal a Gate |

There was also something called "souling," which involved going door-to-door, begging for treats called "soul cakes:"

A soul! a soul! a soul-cake!

Please good Missis, a soul-cake!

An apple, a pear, a plum, or a cherry,

Any good thing to make us all merry.9

A Robert Burns Hallowe'en

According to Ruth Edna Kelley, writing in 1919, "The taste in Hallowe'en festivities now is to study old traditions, and hold a Scotch party, using Burns' poem Hallowe'en as a guide..." I looked up Robert Burns' poem. Here are the last two verses:

In order, on the clean hearth-stane,

The luggies10 three are ranged,

And every time great care is ta'en',

To see them duly changed:

Auld Uncle John, wha wedlock joys

Sin' Mar's year did desire,

Because he gat the toom dish thrice,

He heaved them on the fire

In wrath that night.

Wi' merry sangs, and friendly cracks,

I wat they didna weary;

And unco tales, and funny jokes,

Their sports were cheap and cheery;

Till butter'd so'ns, wi' fragrant lunt,

Set a' their gabs a-steerin';

Syne, wi' a social glass o' strunt,

They parted aff careerin'

Fu' blythe that night.

There are twenty-eight verses in all. If, as Edna suggests, you wish to use it as a guide to host your own "Scotch party," you can find the whole poem here.

If you do, please let me know how it turns out—particularly with regard to the luggies.

Footnotes

1 "A.M.," of course, stands for "ante meridiem," which is Latin for "before midday." Apparently Edna was a morning person.

2 The Celts were "polytheists," which means they worshipped many gods. Of course, at that time the Romans were also polytheists, but the gods they worshipped were clearly superior because they were Roman.

3 It is believed that some Druids survived by using a form of magic known as the "Celtic Mind Trick" to make the Romans believe that "These are not the Druids you are looking for."

4 This tactic was also successfully employed with "Yule," which became Christmas, and "Chocolate Bunny and Egg Basket Day," which became Easter.

5 Because people are basically lazy.

6 If he is unsuccessful, his life may end unhappily—by drowning.

7 Or, more likely, will require the services of a dentist.

8 Especially when a guest set himself on fire.

9 Which, over the centuries, somehow devolved into:

Trick or treat, smell my feet!

Give me something good to eat!

If you don't, I don't care!

I'll pull down your underwear!

10 I know it sounds like something disgusting, but "luggies" are actually bowls, "one with clean, one with dirty water, and one left empty. The person wishing to know his fate in marriage was blindfolded, turned about thrice, and put down his left hand. If he dipped it into the clean water, he would marry a maiden; if into the dirty, a widow; if into the empty dish, not at all." (Actually, that is pretty disgusting—not to mention insulting to widows.)

Saturday, October 3, 2015

Booktoberfest

As a bibliophile and Halloweenophile (biblioweenophile?), it should come as no surprise that I have a large collection of Octoberish books. Here are a few of my favorites—a Booktoberfest, if you will. The cover illustrations are linked to Amazon.com, in case you are interested in purchasing any of them. (And before you ask, no, Amazon is not giving me a percentage, although they should certainly consider doing so.)

When I was very young, my two favorites of all of the books in my parents' collection were Comic Epitaphs from the Very Best Old Graveyards, by Henry R. Martin, and Drawn and Quartered, a paperback collection of cartoons by Charles Addams. I found these books equally frightening and fascinating, as both dealt with death. They were also funny, and they had a profound influence on my sense of humor. To this day, I prefer my comedy the same way I like my coffee: black as the inside of a witch's hat.

I found my own copy of Comic Epitaphs over twenty years ago in a little gift shop in North Tonawanda, New York. It is now out of print, but you can get a used copy through Amazon for as little as ten cents. That seems a ridiculously low price for such comedy gold as: "UNDERNEATH THIS STONE LIES POOR JOHN ROUND: LOST AT SEA AND NEVER FOUND."

I don't have Drawn and Quartered, but I do have several collections of Charles Addams cartoons, including The World of Charles Addams, a huge volume containing hundreds of his best. Here's one of my favorites:

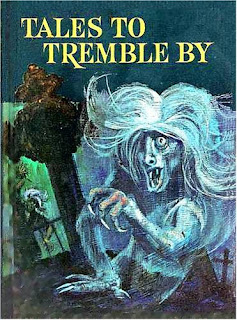

I have a truly horrible book collection—that is to say, I have a truly large collection of books in the horror genre. I began collecting them when I was in grade school. Among the first were two anthologies by Stephen Sutton: Tales to Tremble By and its sequel, surprisingly titled More Tales to Tremble By. These cheap, hardcover "Whitman Classics" were considered children's books, although their contents—frightening tales by the likes of Charles Dickens, Bram Stoker, Saki, August Derleth, and M.R. James—were anything but childish. Both volumes are out of print, but they can still be purchased second-hand through Amazon. The covers alone are enough to give you nightmares.

The author I most associate with Halloween is Ray Bradbury. People think of him as a science fiction writer and yes, he did write stories about rockets and Martians. However, he wrote just as many stories about "things that go bump in the night" (including The October Game, one of the most horrifying short stories I have ever read). Two of his books that are especially evocative of October in general and Halloween in particular are Something Wicked This Way Comes and The Halloween Tree. Both, coincidentally, started out as screenplays, then became books, and finally became screenplays again.

Something Wicked This Way Comes was supposed to be a movie directed by Ray Bradbury's friend Gene Kelly (yes, that Gene Kelly). When none of the studios wanted to make it, Bradbury turned it into a book instead. It's one of those books that grabs hold of you the first time you read it, demands to be reread, and each time you get more out of it. When I was young, I identified with Will Halloway, who is scared to death of growing up. Now I identify with Will's father, who is just plain scared of death. But in the end he comes to a realization: "Is Death important? No. Everything that happens before Death is what counts." Something Wicked This Way Comes was finally made into a movie by Disney in 1983.

The story goes that when Ray Bradbury and his daughters watched the Charles Schulz classic, It's the Great Pumpkin, Charlie Brown, they were greatly disappointed that there was no Great Pumpkin in it. Ray decided he could do better. He talked to his friend Chuck Jones, and the two of them started work on their own animated film, The Halloween Tree, at MGM Studios. Unfortunately, MGM decided to shut down its animation unit, and that was the end of the project. In 1972, Ray published it as a book, and it instantly became a Halloween classic. In 1993, The Halloween Tree was finally made into an Emmy award-winning animated film by Hanna-Barbera, featuring Leonard Nimoy as Moundshroud and narrated by Mr. Bradbury himself.

Finally, if you're looking for a book on the history of Halloween, just this week I came across this little gem: The Book of Halloween, by Ruth Edna Kelley. The book begins with the Celts and ends with contemporary Halloween traditions. By contemporary, I mean 1919; this book is old. It's only ninety-nine cents in the Kindle store, but because it's in the public domain, you can also download it from Project Gutenberg for free. There are several versions. If you buy it from Amazon make sure you get the one with the owl and jack-o-lantern on the cover; it includes illustrations.

Happy Booktober!

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)